I'm officially out of the Sudan now. We actually made it out last Tuesday, but I've been in transit all over the place for the last week and am now getting settled in Western Kenya.

After a month of heavy rains, the reliability of our airstrip in Pagak had become pretty questionable. There is a UN charter flight every Thursday that, for about a hundred bucks, will take you from Upper Nile to Juba in just a few hours. Before the plane touches down, the pilot does a once over to see if the dirt airstrip is muddy or has standing water that will foul the landing gear. Most pilots will just keep the party train moving if they see any sign of water. The Russian guys will land in a swamp. We had a heavy rain a few days before last Thursday's scheduled flight. It's not normally a problem, but the dirt levee guarding the channel that drains all of the water from the high end of the airstrip to the river broke down leaving the airstrip a bit ''marshy.''

At the same time, two of the other guys in the compound were making their exit on foot along the former repatatriation corridor between Pagak and Kuergeng, Ethiopia. In all it is about 25 kilometers or so and takes most of the local Nuer only about three or four hours to walk it. I decided to tag along--I figured that the UNDSS plan would probably leave me in Pagak for an extra week or two and that I would end up walking to Ethiopia anyway. It looked promising for an experience and seemed to be a fitting one for the end of my time in Sudan.

We woke up early, about 5 in the morning. I had my usual breakfast of tea with a half a mug of sugar and powdered cream. I lost my shoes about a month earlier on a previous supply run to Ethiopia and had been wearing blue "floaters", these puffy plastic sandals that I bought for a buck and a half that are moulded to resemble real shoes. They lacked an ankle strap so I fashioned one using duct tape, some nylon rope, and a couple of socks that I cut up for padding. I still had my gumboots, but the water level is too high and the boots would be useless for the trek. When the other guys saw my new homemade shoes, they laughed and Kenneth lent me his sneakers.

As we left Pagak, the trip went as previous ones had, stepping on broken maize stalks and grass to gain traction in the mud. We took a detour around the area with the crocodiles just at the edge of town and continued along the muddy path that leads to the Ethiopian border. Not long after we left the path disappeared and turned into a swamp. The luggage went on heads, and we started wading through it. Within about 10 minutes, the water, which was at about knee level was rising rapidly. For a shorty like me, eventually the water topped out at about my shoulders. Its slow going walking in water. You have to make sure that your feet don't get tangled in the underwater foliage or get snagged on thorns. With the wrong footing it would be easy to dump your luggage from your head into the muddy depths. The rains are also great for taking all of the crap, of which I mean in the literal sense, that usually sits on walking paths and int he bushes and turns everything into a muddy poopy mess.

The border is only a few kilometers away, though it took us about two hours to get there. At the border there is a collapsed bridge spanning a small river that separates two bored looking soldiers from their respective militaries. A month ago, the bridge was easily passable on quad bike but the water was now rushing over the top of it and when crossing, you have to sort of have faith that there will be bridge solidy beneath your feet.

The path that we normally take now looked like a stream. Althogh the fields around it were also flooded, its lack of foliage made it the easiest path for the movement of water. After some time, we reached an actual river that I had remembered from previous trips as a big depression that you drive through, down about 20 feet and then back up again. Now, on either side of the banks there were a bunch of people waiting to cross. Some girls had created a system, by which they would swim giant buckets across the river containing luggage or other carried items away from the water's reach. As you swim across it, you have to cut left hard and hug the tree-line. Immediately the strong downstream current whips you along with it and you have to power through to the other side before you get taken somewhere into what just looks like a tangled mess of trees, vines, and grass. After a few trips back across to pick up other guys in our party, it was back to walking along the flooded path.

About half way, the water level dropped from waist level to nothing and in some parts dried up completely. For these stretches it was punishing. Earlier, the muddy water would help to keep you cool and when you get overheated you just duck beneath its dubious surface. It was now midday and hot as hell. There is mud but, the steamy hot kind kind that you sink down to about your knees and have to pull your leg out with your arms. We only had a few litres of water between us and I was rationing my precious liter with mathematic precision.

After about 7 hours I saw a radio antenna in the distance that lets you know you are about to reach Kuergeng. I poured the last remnants of my water down the ol' gullet and gambled that we would get there soon. What an idiot. Turns out that it was one of those mirages, where you keep walking and it never seems to get closer. By now, the heat, no food, and no water was starting to take its toll. I was grateful for the final stretch-about 3 kilometers of waist high muddy water. I was starting to get heat exhaustion and needed the water to cool off. Only now the water had absorbed all of the midday heat and was like a muddy spa. It took all of my energy to get to dry land and as I staggered out into a village just short of the town, a pissed off Nuer guy started shaking his fist at me. I realized that I had stepped on his levee that kept his village area dry and water was now spilling into it. He saw that I was not really in much of a condition for anything, softened, and pointed out the direction I needed to go to town.

We finally made it. 8 or 9 hours later we reached a hotel restaurant where we had some water, soda, and crackers. My stomach was not really with it enough from the heat exhaustion to have much water, but I forced some in--took half an orange soda and waited to get the sugar levels back to normal. The ride from Kuergeng to Gambella is only about an hour and a half but it was enough to get me back into normal condition. We reached our hotel in Gambella, where I promptly ordered and ate two dinners.

I'll let you know how the trip to Addis, Nairobi, and out here to Nyanza went. The mattatu ride out here was a few hours on a horrible road and one of the wheels fell off, but rural Kenya is beyond sweet. I'm hanging out on a hill overlooking lake Victoria eating 15 cent samosas and giant deep fried Tilapia.

Friday, September 5, 2008

Saturday, August 23, 2008

Updates at Long Last

Hi all. Sorry for the lack of updates for the past two weeks or so. My laptop finally succumbed to the field and is out of commission until I get back. I'm now using an old Dell desktop that is shared amongst three others. That also means that photos are also a no go for a while.

That is not to say that things haven't been lively around here though. After we had our most recent supply drop, we've been having non-stop programming. The week before last, the village health committee got off the ground and we had a three-day, eight-hour training workshop for about 40 people. We trained them on how to deliver health messages in their respective villages and created and action plan for forming a local management committee to take greater involvement in operating the clinic and dealing with issues that come up.

Then we had a second de-worming event at the refugee waystation. This one targeted another 300 children who were given de-worming pills (mmmmm!) and a mosquito net. This was also about the time that we ran out of food at our compound and had been subsisting on scraps of rice and beens for about a week. The waystation has three giant ostriches that are kept there as pets and we started planning for Operation Ostrich Liberation, which is where you sneak into the waystation and eat their pets. Unfortunately, a two-meter tall bird resembling a Velociraptor is unlikely to be hidden in a large shirt.

This week, we had two more training workshops--one for the teachers at the Early Childhood Centers and one for parents. After two or three weeks of bad weather and no supplies the last two weeks have been ridiculously packed. They've also given me a chance to get the documentary filming into high gear. Today, I shot my 33rd hour and have been interviewing parents, teachers, and pretty much everyone I run into. Every person that I've interviewed was either a refugee or child soldier during the war--and this from one of the safest regions during the fighting. I wish I had another two weeks to shore up the footage, there is still a lot to cover and it has only been within the past weeks that I've been able to get where I need to be to talk to people.

Good news though, I am making my escape on Tuesday with the end result of finding my way to Addis Ababa by Saturday. Bad news is that after heavy heavy rains the airstrip is no longer functioning reliably and the road to Ethiopia is covered in a few feet of water. David, Duncan, and I are going to make the trek to Ethiopia on foot through about 30k of what now looks like the Everglades, but with crocodiles instead of alligators. Good news is that once I get to Kuergen and then Gambella, there should be real food! Meat, vegetables, the whole lot. The best news is that after Saturday, I'll be spending my last two weeks going cross country in Kenya and chilling in Nyanza near Lake Victoria. More to come on plans for the developing exodus to food and freedom!

That is not to say that things haven't been lively around here though. After we had our most recent supply drop, we've been having non-stop programming. The week before last, the village health committee got off the ground and we had a three-day, eight-hour training workshop for about 40 people. We trained them on how to deliver health messages in their respective villages and created and action plan for forming a local management committee to take greater involvement in operating the clinic and dealing with issues that come up.

Then we had a second de-worming event at the refugee waystation. This one targeted another 300 children who were given de-worming pills (mmmmm!) and a mosquito net. This was also about the time that we ran out of food at our compound and had been subsisting on scraps of rice and beens for about a week. The waystation has three giant ostriches that are kept there as pets and we started planning for Operation Ostrich Liberation, which is where you sneak into the waystation and eat their pets. Unfortunately, a two-meter tall bird resembling a Velociraptor is unlikely to be hidden in a large shirt.

This week, we had two more training workshops--one for the teachers at the Early Childhood Centers and one for parents. After two or three weeks of bad weather and no supplies the last two weeks have been ridiculously packed. They've also given me a chance to get the documentary filming into high gear. Today, I shot my 33rd hour and have been interviewing parents, teachers, and pretty much everyone I run into. Every person that I've interviewed was either a refugee or child soldier during the war--and this from one of the safest regions during the fighting. I wish I had another two weeks to shore up the footage, there is still a lot to cover and it has only been within the past weeks that I've been able to get where I need to be to talk to people.

Good news though, I am making my escape on Tuesday with the end result of finding my way to Addis Ababa by Saturday. Bad news is that after heavy heavy rains the airstrip is no longer functioning reliably and the road to Ethiopia is covered in a few feet of water. David, Duncan, and I are going to make the trek to Ethiopia on foot through about 30k of what now looks like the Everglades, but with crocodiles instead of alligators. Good news is that once I get to Kuergen and then Gambella, there should be real food! Meat, vegetables, the whole lot. The best news is that after Saturday, I'll be spending my last two weeks going cross country in Kenya and chilling in Nyanza near Lake Victoria. More to come on plans for the developing exodus to food and freedom!

Saturday, August 9, 2008

After a Week of Not too Much to Report, the Plane Comes

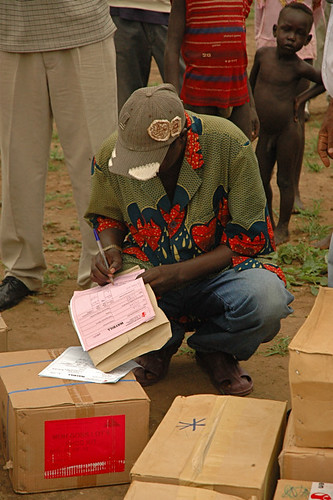

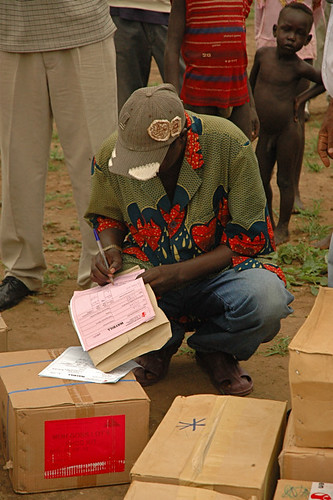

Sorry for the lack of updates, but this past week has been pretty slow. Plagued by a lack of drugs in the clinic and no money for programs or to pay salaries, it had seemed as though things had sort of ground to a halt. However, yesterday our charter plane made it in just before the rains opened up and was able to deliver boxes of much needed drugs from the Southern Sudan Ministry of Health.

Hopefully this means that starting this next week we can get back to our programs. Things were starting to get a touch of the old cabin fever for a while. As in, when you hear an engine of sorts outside the compound, you run over to the fence to gawk at whatever/whoever is passing by. Maybe not the best use of time but it does provide for intermittent entertainment. Even better, we've been watching the Olympics pretty much non-stop on the sat TV in the dining hall. The opening ceremony rocked my world.

Sunday, August 3, 2008

Weekend Supply Drop and Other Fun

On Saturday, our long anticipated charter flight arrived. We were to receive supplies, the most important of which were the drugs for the local clinic. Unfortunately, either due to a delay in the delivery to Juba or some other mishap, the only things on the flight were materials for the Early Child Development program, including about a dozen easel chalkboards. Even worse that meant we had to go our Monday meeting about the drug supply problems with less than awesome news.

Despite the small setback with the charter, the weekend was great. A second UN flight came and the UNICEF officer who had been stranded in Pagak and for the past week had been staying in our compound was able to leave. The UN flight brought somebody important--perhaps a new local administrator, as the flight was greeted with far more people than the usual crowd for a plane landing. The rest of the weekend was marked with non-stop women singing and drum music. Homemade hooch (a rough but potent home brew of yeast and sugar) flowed freely throughout town.

Sunday was a nice day of rest. I slept in until about 10 and just sort of fumbled around for a few hours, not doing anything in particular. Lunch was the usual blend of rice and baked beans. Afterwards though, we finished preparing a goat head for a much better and far more satisfying meal. Lately, we've been keeping the head after the goats have been slaughtered. Usually we send them home with somebody. However, the last two times one of the guys has commandeered it for a special treat--Kenyan style. Preparing it is a two day process. First it is put on a rock or grill on the fire. The heat quickly singes the hair and carbonizes the skin, locking in the moisture on the inside. Then you take a knife an scrape off all of the blackened outer layer and repeat until the outside is at the perfect consistency and the inside is mostly cooked. The next day, the head is slowly cooked in water with some spices and greens. After a few hours you have a delicious spicy soup as well as a bunch of delicious meat. Everything gets eaten and nothing is wasted.

After sitting around eating goat, we had a few cold beers and retired for a nice long afternoon siesta. Sudan can be tough sometimes and development work is painstakingly slow but its nice those times when you can laze back embrace it and have yourself a mini-vacation.

Also, in what would be great news, a malaria vaccine has shown effective results in clinical animal trials and is now set to be tested on human candidates.

Wednesday, July 30, 2008

Back in the Pag

Made it back to Pagak after two nights across the border in Gambella, Ethiopia. The trip there wasn'tt terribly eventful--an hour and a half quad-bike ride to Kuergen across the border and then another hour and a half drive from Kuergen to Gambella.

We arranged to buy two drums of diesel from some lady on a weird side. Our order wouldn't be ready until the following day so we extended what was to be an overnight stay. Gambella wasn't too exciting but it was sure nice to get out of the compound and have some fresh food. Bread totally rocks my world. Hardcore. Unfortunately Wandera was sick most of the time with some sort of pneumonia so after dinner we didn't really do much.

On our final morning we hit each shop that we needed to visit to buy supplies--disinfectant, rope, and the like. We also cleaned out the market buying up as many fresh(ish) tomatoes, cabbage, oranges, and lentils as we could fit on the bikes. We loaded up the LandCruiser, sort of slipped past the bored looking policeman on the road to Kuergan (who could cause problems for anyone trying to bring goods out of the country).

While we were unloading the LandCruiser at the police station in Kuergan where we had stashed the quad-bikes, some nasty looking rain clouds started in on us. You could see where it was just pounding the trees and grass off in the distance. The foreground was nice and clear but the trees about 500 yards away were obscured by a grey black veil of heavy rain. We started off about two minutes before the rain caught up with us. And when it did catch us, things became tough, real fast. The dirt road from Pagak to Kuergan normally passable by quadbike started to flood so we had to race through the bush where the grass would grind into the mud to provide more traction. The hot humid air transformed into a vicious cold wind as we barreled through it on the bikes. And then we started loosing the food. Every few minutes a cabbage, tomato, or some other precious piece of produce would fly off the back and sink beneath the muck somewhere behind us. I had already lost my sandals, headphones, and lens cap on the previous journey and now the delicious food was now going overboard. A giant hole in the cheap plastic bag holding our lentils opened up behind me and I could feel kilogram after kilogram of tiny beans filling the back of my pants and subsequently became a mushy ersatz turd. The cardboard box on the other quad-bike melted in the rain dumping out the disinfectant and other random things all over the place. We hit a bad spot and the bike started to sink down in the mud and despite much coaxing rolled over on its side dumping passenger and produce into a huge pool of mud and feces. Some kids though, watching with amusement our slo-mo disaster, were kind enough to come help us right the bike and retrieve the lost goodies.

We made it back to Pagak without further incident. Pagak bridge was not yet flooded so we were able to just roll on over. In another week though it will become impassable and the bikes will have to be floated across on an oil drum raft. But for now, we have another few weeks worth of fresh food and two months of gas!

Saturday, July 26, 2008

Off to Ethiopia Again

Heading out in a few minutes to find some food and fuel across the ol' border. I should be back sometime tomorrow or the next day. Hooray for vegetables and lights!

Thursday, July 24, 2008

Night time is nice

Once the generator dies at night, it becomes so dark that you can see more stars than in most places in the world. The air is devoid of pollution and there is literally no artificial light for hundreds of miles. The Milky Way is pretty sweet.

On an entirely different note, you should totally check out this website

The Rains Cometh!

When I woke up yesterday, there was something crazy flapping behind the curtain. I pulled it away and found this little guy just sort of watching things from the wrong side of the window.

We had a pretty gnarly thunderstorm during the night and apparently he decided that my room would be good shelter from the storm. Fine by me. I opened up the little glass slats that is my window and let him go on his way.

In the morning, I headed down to the clinic to help out and try to do some damage control on the drug shortage issue. While I was there, I helped one of the staff reorganize the store-room into something a bit more coherent. Previously, all of the drugs and supplies were just sort of stored haphazardly in quarter full cardboard boxes around the tiny room. As we started shelving the supplies, I realized quite how out of drugs they were. Aside from a few bottles of antibiotics and Lidocaine, not much else was there. For some reason, though, there was a ton of dextrose saline bags meant for IV drips. Which is great, but it’s tough when there isn’t much else to give.

On my last few visits, I’ve been meeting with patients, which is strange, since many people assume that I’m a doctor because I am white. Which could be bad given that I don’t have any drugs. Two days ago I visited a guy with severe advanced Pneumonia. If you put a stethoscope up to his back, his left lung sounded fine but not much was going on in the right one. Not even much of a rattle or wheeze. Not good. He’s been on, you guessed it, an IV drip as well a high dose of antibiotics. Yesterday the staff was feeding him a plate of brown gruel covered with cloudy murky water.

After I returned to the compound, the sky opened up. Not quite like before, but much worse. It was only about 12:30, but the sky looked like it was about eight at night. Not good. Within about 20 minutes, everything started flooding.

There is a shallow drainage channel that funnels the water from the center of the compound out onto the airstrip. The problem occurs when it comes down faster than the channel can handle. One side of the compound, the one on slightly higher ground, was fine. As for the other one, well…

Oddly enough, by the end of the day the water was gone and things were just back to mudtown as usual. The heavy rains that were supposed to have started weeks ago now seem to be upon us after a brief delay.

We had a pretty gnarly thunderstorm during the night and apparently he decided that my room would be good shelter from the storm. Fine by me. I opened up the little glass slats that is my window and let him go on his way.

In the morning, I headed down to the clinic to help out and try to do some damage control on the drug shortage issue. While I was there, I helped one of the staff reorganize the store-room into something a bit more coherent. Previously, all of the drugs and supplies were just sort of stored haphazardly in quarter full cardboard boxes around the tiny room. As we started shelving the supplies, I realized quite how out of drugs they were. Aside from a few bottles of antibiotics and Lidocaine, not much else was there. For some reason, though, there was a ton of dextrose saline bags meant for IV drips. Which is great, but it’s tough when there isn’t much else to give.

On my last few visits, I’ve been meeting with patients, which is strange, since many people assume that I’m a doctor because I am white. Which could be bad given that I don’t have any drugs. Two days ago I visited a guy with severe advanced Pneumonia. If you put a stethoscope up to his back, his left lung sounded fine but not much was going on in the right one. Not even much of a rattle or wheeze. Not good. He’s been on, you guessed it, an IV drip as well a high dose of antibiotics. Yesterday the staff was feeding him a plate of brown gruel covered with cloudy murky water.

After I returned to the compound, the sky opened up. Not quite like before, but much worse. It was only about 12:30, but the sky looked like it was about eight at night. Not good. Within about 20 minutes, everything started flooding.

There is a shallow drainage channel that funnels the water from the center of the compound out onto the airstrip. The problem occurs when it comes down faster than the channel can handle. One side of the compound, the one on slightly higher ground, was fine. As for the other one, well…

Oddly enough, by the end of the day the water was gone and things were just back to mudtown as usual. The heavy rains that were supposed to have started weeks ago now seem to be upon us after a brief delay.

Labels:

Pagak,

Southern Sudan,

Upper Nile State

Monday, July 21, 2008

Rough Day

So yesterday the plan was to head down to the ECD center with some meds, mosquito nets, and registration forms to deworm the ECD kids. That was the plan. And deworm we did. About 200 parents and kids showed up for the event.

Unfortunately, the procedures for the actual registration and de-worming were a bit...ahem...underdeveloped. And by underdeveloped I mean chaotic. It started out simple enough. Duncan and Jaffar gave a talk about malaria, how it is transmitted, and how people can protect themselves. They gave a demonstration on how to put together and properly use one of the Long Lasting Insecticide Treated Nets. Later we divided everybody up into about four or five groups and one or two of us manned each one with local translators (except for Judith who had to enlist the help of some of the students from her social marketing youth group). We wrote down the name of each child and parent we treated, checked it against our ECD list, and gave each de-worming pills. We gave the youngest children got a mosquito net. Despite the disordered craziness, it was going great.

That is until the nets and the meds meant for the ECD kids ran out. Leaving a lot of very pissed off people wondering where their goodies were. There were even people there from Ethiopia who had heard about the even through the vast informal network and had walked with kids all the way from Kuergen--about a six hour walk. When we started to wrap up, most just begged for any of the goods. It was terribly difficult to tell them that we only had enough drugs and nets for the young kids that attended the center. Many though, were a bit more vociferous in demanding the nets and the meds. It's entirely understandable, they walked from who knows where, waited for several hours, watched others get meds and nets, only to be denied at the end. On the other hand it got a bit nasty as pleas turned into yelling in some cases. I'm not sure who did it, but I definitely got whacked over the head with a stick or a piece of rope while I was kneeling in the other direction.

As I mentioned previously, aid dependency is a very real problem and yesterday, thanks in part to some disorganization and poor planning, it reared its nasty side. The trick of it all is to somehow continue to ensure that basic goods and services are in some way being produced and distributed, even as NGO's shift their programming away from relief aid towards development. And avoid getting smacked in the process.

Labels:

Development,

Pagak,

Southern Sudan,

Upper Nile State

Sunday, July 20, 2008

Security Level in Upper Nile Increased...

...due to increased river pirate activity. Seriously, river pirates? What's that about?

Weekend of Mud

We've had non-stop rain this weekend...which means non-stop mud. Unfortunately, it also means that not much can really be done. Except watch the UFO and alien marathon on the National Geographic--all day. We have satellite TV while the generator is on for its few hours today. The best we can come up with is a UFO marathon? Seriously. In the last five minutes, I heard the phrase "moon germs." Moon germs. Didn't National Geographic used to be a respectable programming network? The other option is the early 1990's movie "The Road to Christmas". Which may be how I spend the day if I have to watch another dramatic recreation of alien experimentation.

Anyhow, here are some pictures of the old mudpound from the weekend. If anyone is interested, I should be an expert on aliens by the the end of the day.

Courtesy of Miss Judis:

On the bright side, at least the rain washed off our dinner! Potato Time!

Labels:

Mud,

Pagak,

Southern Sudan,

Upper Nile State

Saturday, July 19, 2008

The Drug Shortage Continues

Yesterday, we met again at the PHCC to discuss the complete shortage of drugs. The supply of the critical drugs like Quinine is no worse today than it was yesterday (Still nearly at 0), but tensions over it have been steadily increasing. The clinic staff is anxious over the clinic's condition. And rightfully so. They've also been working without salary for quite some time now. Last year, when the same issue came to a breaking point, one of our staff was arrested by the local police for not suppling the clinic with drugs.

I'm afraid, that this is where things are headed again. That is, unless we get the drugs here very soon. One of the community health mobilizers, a 20 year veteran of the war, likened the situation to sending soldiers into battle with no bullets. It reminded him of the time when he was given only two bullets for his rifle before a large engagement, fired them off within the first few minutes and had to run away. That's not something you want your operation compared too. Another second problem is lights. If a patient comes in at night--too bad. Without a generator to supply electricity, the staff have to work by flashlight or tell the patient to return in the morning. SC had provided the clinic with a solar powered lamp, but it has gone missing in action--likely stolen and sold in some market somewhere.

The problem is a complex one. It begs the question--what are the roles and responsibilities of NGO's in post-conflict countries? Especially those that have long existed as a humanitarian emergency that required the direct distribution of aid. Duncan raised an interesting point, that when John Garang signed the CPA in 2005, it signaled the end to most organizations relief operations in Sudan. Many have packed up and left, but others like SC are switching their programming from relief to development. Aid dependence is a legacy of that time that will continue to affect life far after the end of the conflict. And that's why this drug problem is becoming so acute. The bureaucratic foul-ups and transport issues that have prevented the drug distribution aside (and I assure you there have been many), the current problem highlights the increasing divergence of community expectations and the responsibilities of organizations as they view themselves. Community ownership of NGO programming and aid dependence are competing values--you can't have both. At the same time, with an infant government of Southern Sudann (GoSS), public goods are in short supply and organizations cannot entirely abandon certain relief efforts wholesale. Although that was not the intention of the drug shortage at the clinic, it has functioned as such. One day the clinic had drugs, the next day it didn't.

And yet, what happens if a shipment of drugs is able to get through in the next month? What happens after the rush on drugs a month later when the clinic is again empty? You are back to square one--and that seems to have been the case during the period when our staff was arrested over the shortage a year ago and the situation today. Who is to say that won't be the situation again a year from now? Whose responsibility is it ultimately in the long run to keep drugs stocked at the clinic.

We talked about our two-pronged approach. On the one hand, we are trying to get the drugs here. Some are sitting somewhere in the region, but apparently there is no way to get them here given the weather. The roads are flooded. The other is where the idea of a Village Health Committee comes in. Curative medicine is critical. A person becomes sick with a life threatening disease and they need drugs and treatment to recover. Otherwise they die. However, so many of the diseases here are preventable. Not entirely, but with better sanitation facilities, knowledge of the spread of disease, and basic precautions the rates of infection will decrease. If you can involve community stakeholders to become directly engaged in managing and solving these issues than you have a program that is sustainable. When NGO's eventually leave,or the drug supply again runs out again, the region will be less likely to plummet back into a health disaster. The problem is, thats a hard place to get to.

The drug supply issue is threatening to undercut the VHC program. Why should individuals help us mobilize others to spread awareness of a clinic's services if the community can't receive treatment there? The short answer goes back to the importance of shifting attitudes towards accepting and using good health practices. This would continue to reduce of the burden on the curative side of managing endemic health problems and makes for a better, self-sufficient society. Yet this is something that is, at its core, an exercise dependent upon trust-building. Without resolving the drug issue expediently, this trust is going to be in limited supply.

Labels:

Development,

Pagak,

Southern Sudan,

Sudan,

Upper Nile State

Thursday, July 17, 2008

Drugless in Pagak

Today, Duncan, Titus, Jaffar, and I went to the local Payam administrators to try to get them on board with the creation of the Village Health Committee. They gave us a tentative go ahead and agreed to call all of the local Boma (village) chiefs together tomorrow so we can discuss the process of selecting a man and woman to represent each Boma in the committee. We were, however, lectured at length about the lack of drugs at the Public Health Community Center (PHCC). It seems that not only has there been a complete lack of drugs at the clinic, but also the staff have not been paid salary in some months. The drug shortage is starting to reach a critical level and risks jeopardizing the programs we are working on.

Earlier, I went to the clinic with Jaffar to check up on a woman who was admitted yesterday with a severe case of cerebral malaria. The problem is that the PHCC is at a total lack of drugs, including the quinine that is necessary to treat Malaria. Cerebral malaria is what happens when malaria goes from bad to worse. The parasite crosses the blood brain barrier and the infected individual will no longer respond to a strong dose of prophylaxis (which can only treat malaria while it is still in the bloodstream. Without treatment it leads to coma and eventually death. Despite the lack of quinine, someone in her family was able to buy a dose in the local market.

Jaffar and I went to the two small shops where drugs are sold to see if we could track down some quinine. You need about four or five doses to make a decent recovery from such a severe case (Each dose contains six mini-doses that are administered intravenously). Although the woman had received one, the chances are high that she would soon relapse into a severe case or, even worse, one that is quinine resistant. The first chemist we went to was not only out of quinine, but also most antibiotics and other drugs that would be helpful in treating severe cases. The second chemist had a small supply of quinine at about 60 Birr (about six bucks) a dose. I really wanted to buy the woman a second dose, but with my Ethiopian currency supply dwindling, I came up about a dollar short. Hopefully the woman's family can come up with enough cash for her to finish the treatment.

Malaria season is just kicking into high gear. Last August, of the hundred or so cases at the clinic, seven people died. This August, I am going to try to increase my ground time at the clinic and cover the Malaria season in video.

The other case was a young girl who was bitten by a snake. Again, the lack of drugs means that she will not be able to receive the anti-venom she needs to make a reasonable recovery. They started her on a course of antibiotics to prevent infection, but once necrosis sets in she will have to be sent to a better clinic, perhaps in Malakal (quite some distance from here).

The drug situation is a tough one. Even if we were to have a ready supply of drugs in Juba, like most other supplies, it is near impossible to get them up here. A better solution would be to purchase them in Ethiopia and transport them overland by LandCruiser and quad bike. Unfortunately, the government has a seemingly unofficial policy of "Ethiopian drugs are for the Ethiopians" and it is impossible to get a large quantity of drugs cleared by customs. What needs to happen is a huge stock up of drugs at a central field depot where the clinics can make a long (but possible) LandCruiser trip to pick them up as needed. Especially in anticipation of malaria season. Unfortunately, given the realities on the ground and the difficulties of transport, the drug supply issue is one that will not be resolved anytime soon

Labels:

Development,

Pagak,

Southern Sudan,

Sudan,

Upper Nile State

Home Sweet Home...at Least for Another Seven Weeks

The town of Pagak is literally in the middle of nowhere. To get here, you either need to hire a private plane, bum a ride on a cargo flight, or drive across Ethiopia to the border and hop on an ATV or a dirt bike for the rest of the way. If you can manage to get here, Save the Children has a pretty permanent looking compound here right next to the dirt airstrip.

From the airstrip you walk down a dirt "road" that has been gutted with deep channels from our LandCruiser as it tries to avoid getting stuck in the mud. You walk down said muddy path for about 30 seconds and knock on the corrugated tin sheet metal that forms the compound gate . Eventually a guard will wander up, unlock the door and let you in.

Inside, we have about 10 or so little buildings, tents, huts, or other forms of enclosed space to work out of or get away from the rain. The largest is the Dining Hall (or Dining Hut). Its a sweet wood and mud room covered with grass and topped off with a giant UNHCR tarp. About once a month, some of the local staff re-muds the walls to fill in the cracks and crumbled exterior. Outside are the two satellite dishes that provide communication with the outside world. Provided there are no clouds or rain, that is. Inside, we have our meals (Spaghetti, rice, and baked beans--everyday!) as well as a TV and dart board. I've been hitting the darts pretty hard. When the generator kicks off at noon, in the evening, and at night, there's not much else to do. I've unwisely already long burned through my supply of books. When the office gets too full of people, the overflow head into the dining hall and set up shop.

The office itself is actually pretty small--just a one room tukul. But inside we have five desks, printers, and most importantly--wireless internet. Although it becomes impossible to use once more than a few people are using it, its one of those things that you don't fully appreciate until the generator kicks off. Because of the presence of the mighty internet, we usually are in the office until about 11 at night officially working on projects, or unofficially just messing around.

From the door of the office, you can take the network of rock paths (as the rain turns all of the mud into a deep deep soup) to either the kitchen or one of the several rooms in the compound.

Breakfast is usually pancakes or mandazi (fried bread--like an unsweetened donut) and always some hot tea with powdered milk. Nyamone cooking up some pancakes:

There are two types of living quarters--brick rooms and tukuls. I suppose three types--we also have two small two-man dome tents covered with tarps for overflow. All of the rooms are arranged around the perimeter of the compound, which means that at night you can hear just about everything outside--blasting Teddy Afro music, local police on patrol, and people chatting away in their tukuls.

The winner of the compound amenities game is the hot water. That's right, hot water. A while back, someone had the presence of mind to cut in half one of the many old oil drums that we have and use it to heat water throughout the day.

All you have to do is take your bucket walk over to the oil drum, scoop up some of the water, add some disinfectant to kill of all of the worms, bacteria, and all the other crap living in it and...bam! You've got yourself an instant shower my friend.

With all of the crazy moving around that I've been doing lately and the old luggage crisis at the beginning of my trip, I didn't realize until today that I've been here for over a month now. I've started to settle in pretty well--hot water, mud, wandering goats and all. Seven weeks to go!

Labels:

Development,

Pagak,

Save the Children,

Southern Sudan,

Sudan,

Upper Nile State

Wednesday, July 16, 2008

Way to Go Mugabsters

Not only has Robert Mugabe managed to intimidate his way into winning the presidency unopposed, but he's also managed to destroy the Zimbabwean economy more than economists had previously thought.

The last estimate Zimbabwe's inflation rate was pegged at around a staggering 170,000% in February. Today it turns out that official assessment was revised upwards a little bit. To a mere annual inflation rate of 2,200,000% This means that, while a Zimbabwean dollar would have bought you a US dollar and then some in 1980, you now only need a mere 250,000,000 of them to buy one today. Way to go!

Tuesday, July 15, 2008

Gettin' Some Community Action

This morning, Duncan, Judith and I went to the PHCC to meet with some previously trained Village Health guys to talk about forming a community health group to be established and run by local people with our support. As was the case with the women's group, its incredibly difficult to organize something like that within a community of people who have had public goods provided in an emergency relief situation. It doesn't help that in a place where we are wondering if it is ready for ox-powered agriculture or not, basic needs are still so pressing that people need food before they are willing to talk about organizing for things such as a community education program. And many are not getting it. Likewise, its difficult to organize a of individuals to become the primary stakeholders in a group and are willing to take ownership and leadership in its management and direction, especially on a volunteer basis. After decades of direct relief during the war, the transition from relief to development is, at times, unbearably challenging. But you have to start somewhere, even if its with a defunct community group. The objective is to organize a group of core individuals who will in turn lead the mobilization of a larger group--family, village etc.--and give them the support necessary such that the program is sustainable without the direct management by an NGO. It is not to directly provide the services or goods themselves. That way, when the NGO packs up and leaves, those services or goods can be provided sustainably by the local community. Or so the theory goes.

From there, I had afternoon English class. Lot's of "I am Bret" "He is Titus" "He is happy" "She is not sad" and the like. We also played a few games with flashcards of animals and vegetables. We had a 10 minute diversion over whether or not there is cabbage in Pagak. The best part of class was, though that I found a Sudanese guy who is pretty good at English and starting tomorrow will teach the class with me. I hope that if we can get him in front of the class teaching, he can maybe take over for me when I leave. It also still leaves me with about six weeks for crash course teacher training and plenty of time to come up with a curriculum for absolute beginners and the necessary materials for such a course.

I rode the good feelings on over to the NCDS compound where Judith was having her youth group meeting for a social marketing piece on the importance of education. The discussion went fine and I was feeling good until the session started to wind down. One of the guys about my age had said during the discussion that he was willing to come to these sorts of programs and support them because while he was living in Ethiopia he had to go to school barefoot and without supplies. Sometimes he just wouldn't go. Eventually a Catholic organization gave him shoes and school supplies and he seems to have a sincere desire to work with local groups on community improvement. Pretty groovy. Until he pulled me aside afterwards and asked me if I could find him some glasses because he really needed them. How do you respond to that? There are a lot of great groups that collect used glasses donations and ships them to areas around the world where they are needed. Unite for Sight provides people in developing areas with free eye exams and corrective surgery. I had to tell him that I just don't have any glasses but that I would look into some things and get back to him tomorrow. I thought maybe there is an organization or something that I could contact and while I couldn't get anything to him per se, maybe we could work something out in the future for the rest of the community. The sad reality is that even if there were a supply of glasses ready to be distributed and sitting in Juba, the only way to get anything into Pagak is via a $3000 charter flight from Juba or via Addis Ababa and a punishing overland trip across Ethiopia. Sudan's infrastructure is just so poor that even something like eye glasses will remain unavailable in Upper Nile for quite some time.

In Cambodia, these things really wore me down. I remember the girl who would learn your name and then find you everyday to ask for just a little bit of money. Over the years I've become a bit hardened to people asking me for things or perhaps just desensitized. But still, on days like today, somebody asks me for a pair of glasses and I find myself down, brooding in the dark somewhere and sad for what I will have to tell him tomorrow. He took a piece of paper at the end of the meeting and mentioned something about writing me a letter. I hope for my own sake that I misheard him. But I know that is probably not the case.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)